Global Treaty Needed to Halt Deep Sea Mining, Greenpeace Investigation Concludes

Deep sea mining is leading private mining firms and arms companies to carve up the seabed in plans that should be halted by an international ocean treaty, argues a new report from Greenpeace.

The investigation, Deep Trouble: The murky world of the deep sea mining industry, decries the increasing use of the ocean floor by large corporations, such as U.S. arms manufacturer Lockheed Martin, to mine metals and minerals. Only several private sector companies with shell-organizations, or "operating through complex and opaque structures of sub-contractors, partnerships or subsidiaries," received 30 contracts to mine from the International Seabed Authority, a consortium with no environmental or assessment process that acts as the overseeing organization on seabed mining contracts. The ISA has never rejected a bid for mining.

For every contract the ISA issues, it receives $500,000. Greenpeace finds the setup to be a potential conflict of interest that undermines environmental regulation at the state and national level. It also unfairly allocates the natural resources of the ocean, to the point where some corporations partner with small island states such as the Micronesian country of Nauru, but the companies reap the benefits of extraction, while the nation-states are left with all the liability.

In 2019 deep sea mining and shipping firm Nautilus went bankrupt, leaving its partner state, Papua New Guinea on the hook for cleanup expenses. Now, according to The Guardian, Papua New Guinea is one of many nations calling for a moratorium on deep sea mining.

And the potential for environmental destruction is evident, says Greenpeace.

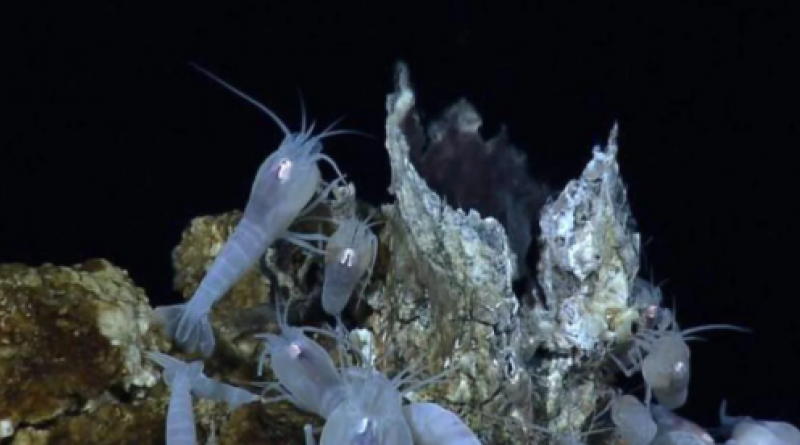

"Deep sea mining will cause serious and irreversible damage to the ocean biome, risks driving biodiversity loss and could potentially damage an important carbon sink: the deep ocean," the executive summary of the report notes. Dumbo octopuses, deep-sea corals, and the endangered scaly-foot snail are all potentially at risk of extinction.

In some areas the ocean floor contains poly-metallic nodules, which contain within them manganese peroxide, a substance used in bleaching powder, and cobalt, nickel, copper, titanium — metals commonly used in smartphones.

Just like a rocky garden, the life around the nodules is more abundant. And deep sea mining leaves tracks on the ocean floor that stay in place for decades, disrupting the area's natural processes, and are harmful to the few species of life that survive on the abyssal plain.

DeepGreen Metals Inc., one of the companies with an ISA approved mining contract, told The Guardian in a response to Greenpeace that deep sea mining could supply "critical minerals for the global transition off fossil fuels at a fraction of environmental and social costs associated with metal production from conventional land ores."

Greenpeace is calling for an international ocean treaty, where nations reuse and recycle the existing supply of minerals and metals, instead of opening the ocean floor to extraction.

"We think the deep sea ocean should be off limits because it is not possible to have good enough environmental rules," Louisa Cannon, lead author of the report told The Guardian.

"Scientists are warning of irreversible harm and potential extinctions. The ISA is supposed to be protecting the oceans and it's not doing its job."

9 December 2020

EcoWatch