Glaciers in Himalayas melting at ‘exceptional’ rate, scientists warn

Acceleration of ice loss due to climate crisis could threaten water supplies for ‘hundreds of millions’ of people

Glaciers in the Himalayas are shrinking far more rapidly than glaciers in other parts of the world, threatening the water supply of millions of people in Asia, new research warns.

The study, led by scientists at the University of Leeds, found that in recent decades, Himalayan glaciers have lost ice 10 times more quickly than they have on average since the Little Ice Age, when glaciers expanded around 400-700 years ago.

The ice loss is occurring so quickly, the research team described the rate as “exceptional”.

The researchers reconstructed the extent and ice content of 14,798 Himalayan glaciers to reveal how large they were during the Little Ice Age. The model revealed that the glaciers we see today have now lost around 40 per cent of their area, shrinking from a maximum of 28,000 square kilometres to around 19,600 sq km today.

During that period, they are believed to have lost up to 586km cubed of ice – the equivalent of all the ice contained today in the central European Alps, the Caucasus, and Scandinavia combined.

Dr Jonathan Carrivick, one of the study authors and deputy head of the University of Leeds School of Geography, said: “Our findings clearly show that ice is now being lost from Himalayan glaciers at a rate that is at least 10 times higher than the average rate over past centuries.

“This acceleration in the rate of loss has only emerged within the last few decades, and coincides with human-induced climate change.”

The Himalayas are home to the world’s third-largest amount of glacier ice after Antarctica and the Arctic, and are often referred to as the world's “Third Pole”.

The researchers warned that the acceleration of melting of Himalayan glaciers has “significant implications” for hundreds of millions of people who depend on Asia’s major river systems for food and energy.

These rivers include the Brahmaputra, Ganges and Indus.

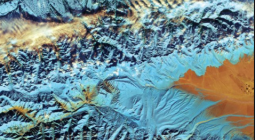

The team used satellite images and digital elevation models to produce outlines of the glaciers’ extent 400-700 years ago and to reconstruct the ice surface.

The satellite images revealed ridges that mark the former glacier boundaries and the researchers used the geometry of these ridges to estimate the former glacier extent and ice surface elevation.

Comparing the glacier reconstruction to the glacier now, the researchers determined the volume and hence mass loss between the Little Ice Age and now.

Himalayan glaciers are also declining faster where they end in lakes, which have several warming effects, rather than where they end on land. The number and size of these lakes are increasing so continued acceleration in mass loss can be expected, the scientists said.

Similarly, glaciers which have significant amounts of natural debris upon their surfaces are also losing mass more quickly: they contributed around 46.5 per cent of total volume loss despite making up only around 7.5 per cent of the total number of glaciers.

Dr Carrivick said: “While we must act urgently to reduce and mitigate the impact of human-made climate change on the glaciers and meltwater-fed rivers, the modelling of that impact on glaciers must also take account of the role of factors such as lakes and debris.”

Co-author Dr Simon Cook, senior lecturer in geography and environmental science at the University of Dundee, said: “People in the region are already seeing changes that are beyond anything witnessed for centuries.

“This research is just the latest confirmation that those changes are accelerating and that they will have a significant impact on entire nations and regions.”

The research is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Harry Cockburn Environment Correspondent

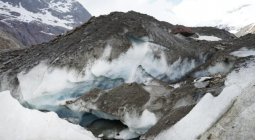

Cover photo:

Khumbu Glacier in northern Nepal. Ice melt is now occurring in the Himalayas 10 times faster than in previous centuries