Cooling down Europe’s heating system.

If we want Europe to go carbon neutral, we must stop manufacturing and selling technologies based on oil and gas – starting with heating systems, write Davide Sabbadin and Melissa Zill.

Davide Sabbadin is a policy officer at the European Environmental Bureau (EEB). Melissa Zill is programme manager at ECOS. Together, the EEB and ECOS lead the Coolproducts campaign – a coalition of NGOs working to ensure better products for consumers and the planet.

The decarbonisation of Europe’s heating and cooling system is set to dominate the climate debate in 2020.

Today, the heating of buildings and the production of hot water is responsible for half of the EU’s annual energy consumption and a third of its CO2 emissions.

From renewable energy to building renovation, there is growing pressure to implement sustainable solutions. But despite a spike in new technologies, Europe’s approach to decarbonisation has so far been one step forward and two steps back.

Phase out fossil-fuel boilers by 2030

So long as fossil fuel-fired space and water heaters continue to be produced, sold and installed in our homes, it’s difficult to envisage a carbon-neutral future for Europe.

Fossil fuels still generate over 80% of Europe’s heat supply, with gas boilers being the single largest source. Many countries want to reverse this trend, promising a shift to renewable energy and carbon neutral technology such as heat pumps, which would lower energy bills in the long run.

But progress is slow as the continued production of fossil fuel technology and infrastructure makes the uptake of new technology more challenging by the day.

The main problem is that clean solutions are at a disadvantage compared to fossil fuel technologies. Currently, it is more expensive to replace a gas boiler with a more efficient system than to replace it with another gas boiler. Financial incentives are very rare, and installers are not always aware of the alternatives.

When green solutions are not actively incentivised, consumers are unlikely to make the switch and are left with false solutions instead. Already manufacturers are promoting condensing gas boilers as a clean alternative to non-condensing gas boilers, even though truly clean technologies based on renewable energy are available.

Finally, installing a new gas boiler today means that it will be in use for an average of 10 to 20 years. Scientists have done the math, and it turns out we don’t have that much time to reduce carbon emissions.

If we want to decarbonise heating, it’s clear that we need a holistic approach that addresses all these issues. The least efficient heating systems should be gradually phased out of the EU market, with the last fossil fuel boiler being sold no later than in 2030.

Putting an end date on the production of fossil fuel technology would give both consumers and manufacturers time to prepare for the switch. Realistically, this means that the European Commission should start discussing and drafting proposals before the end of this year, as part of its flagship Ecodesign Directive.

Energy efficiency, renewables and heat pumps

The transition to carbon-neutral heating systems needs to go hand in hand with building renovation.

An EU-wide subsidy scheme for insulation and double-glazing is a key step to make our houses more comfortable and energy efficient. A recent study found that the widespread renovation of buildings could save 36% of their energy consumption by 2030.

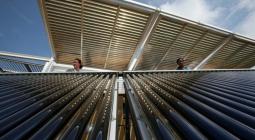

Well-insulated houses would also accelerate the uptake of new solutions, such as electric heat pumps, which in most cases can now replace conventional gas boilers.

Currently, heat pumps are present in fewer than 10% of all buildings, but the market is growing rapidly. The EU stock delivered 164 TWh of final energy savings and produced 128 TWh of renewable energy in 2018, which resulted in 32.8 Mt of CO2 emissions saved – the equivalent of the combined emissions of Cyprus, Latvia and Luxembourg in 2017.

Not only can heat pumps be carbon-neutral, but they are also among the most flexible technologies available. They can run efficiently on geothermal, solar and wind power, keeping the heat in storage tanks and generating electricity for the house when it’s needed – even when sources of renewable energy are not dispatchable.

If large enough, they can also be integrated in district heating systems, where they heat or cool entire areas.

The hydrogen revolution?

Not so fast. It’s tempting to believe that hydrogen and other forms of renewable gas represent the future of heating. But hydrogen boilers could be a very costly gamble.

Currently, the availability of green hydrogen – generated through electrolysis from renewable energy – is still limited, and its cost is considerably higher than that of both fossil gas and renewable electricity. A more common form of hydrogen is produced from fossil gas, including through fracking, but this option would obviously not help reducing emissions.

Building an infrastructure fit for hydrogen without first securing enough renewable energy supply is a risk Europe cannot afford to take – one which would clearly undermine its decarbonisation efforts.

Hydrogen would be more valuable in a supporting role, as part of efforts to decarbonise energy-intensive industries, such as the steel industry, where the energy demand would be comparatively lower and where electrification may be more challenging.

As calls for climate action grow and we edge closer to the point of no return, policymakers have very little time and room for mistakes. The focus should be on realistic and available solutions that would help us move away from fossil fuels altogether. The time for debates is over – the steps towards decarbonisation must be taken now.

Euractiv