Climate change: Thousands of penguins die in Antarctic ice breakup

A catastrophic die-off of emperor penguin chicks has been observed in the Antarctic, with up to 10,000 young birds estimated to have been killed.

The sea-ice underneath the chicks melted and broke apart before they could develop the waterproof feathers needed to swim in the ocean.

The birds most likely drowned or froze to death.

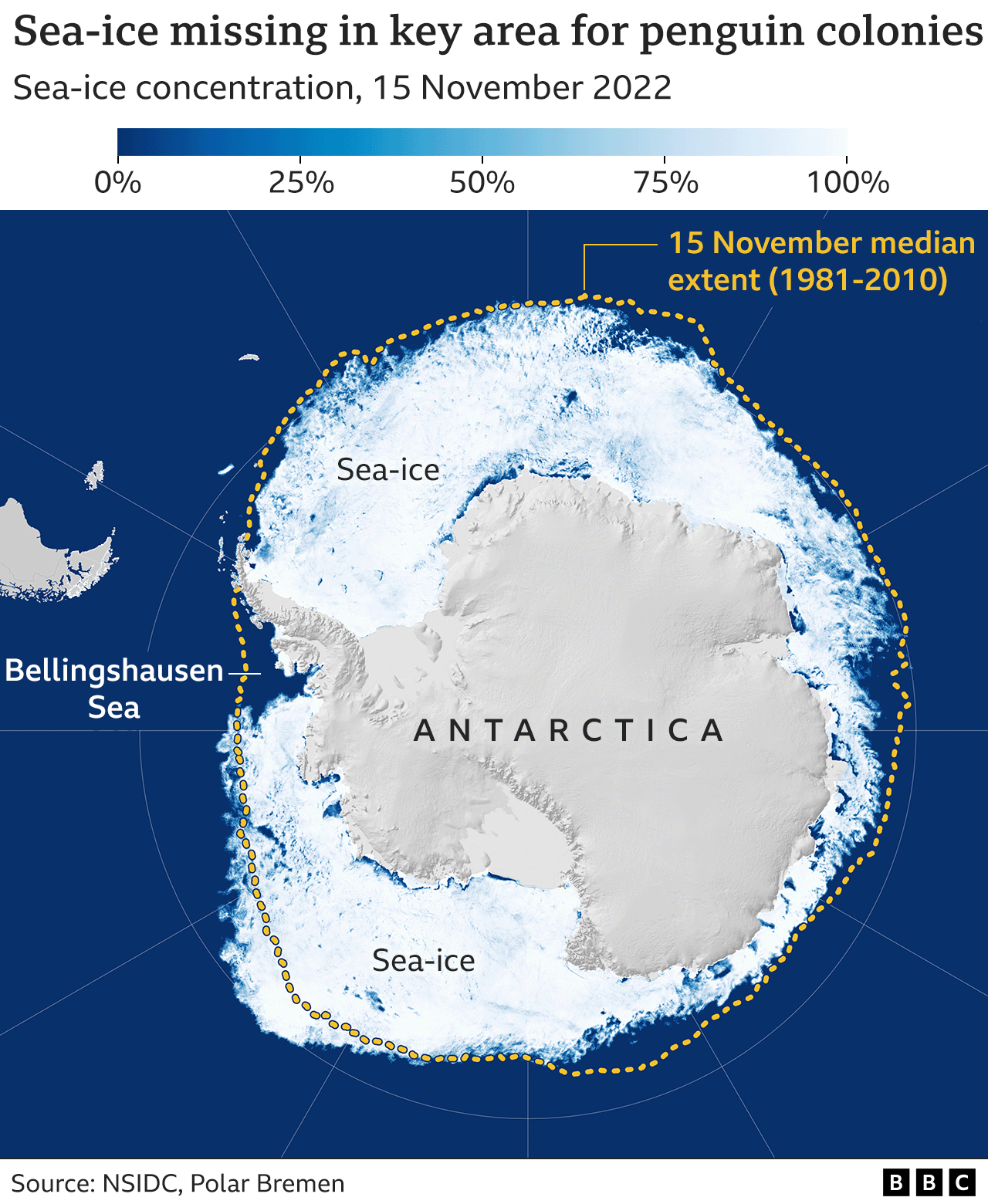

The event, in late 2022, occurred in the west of the continent in an area fronting on to the Bellingshausen Sea.

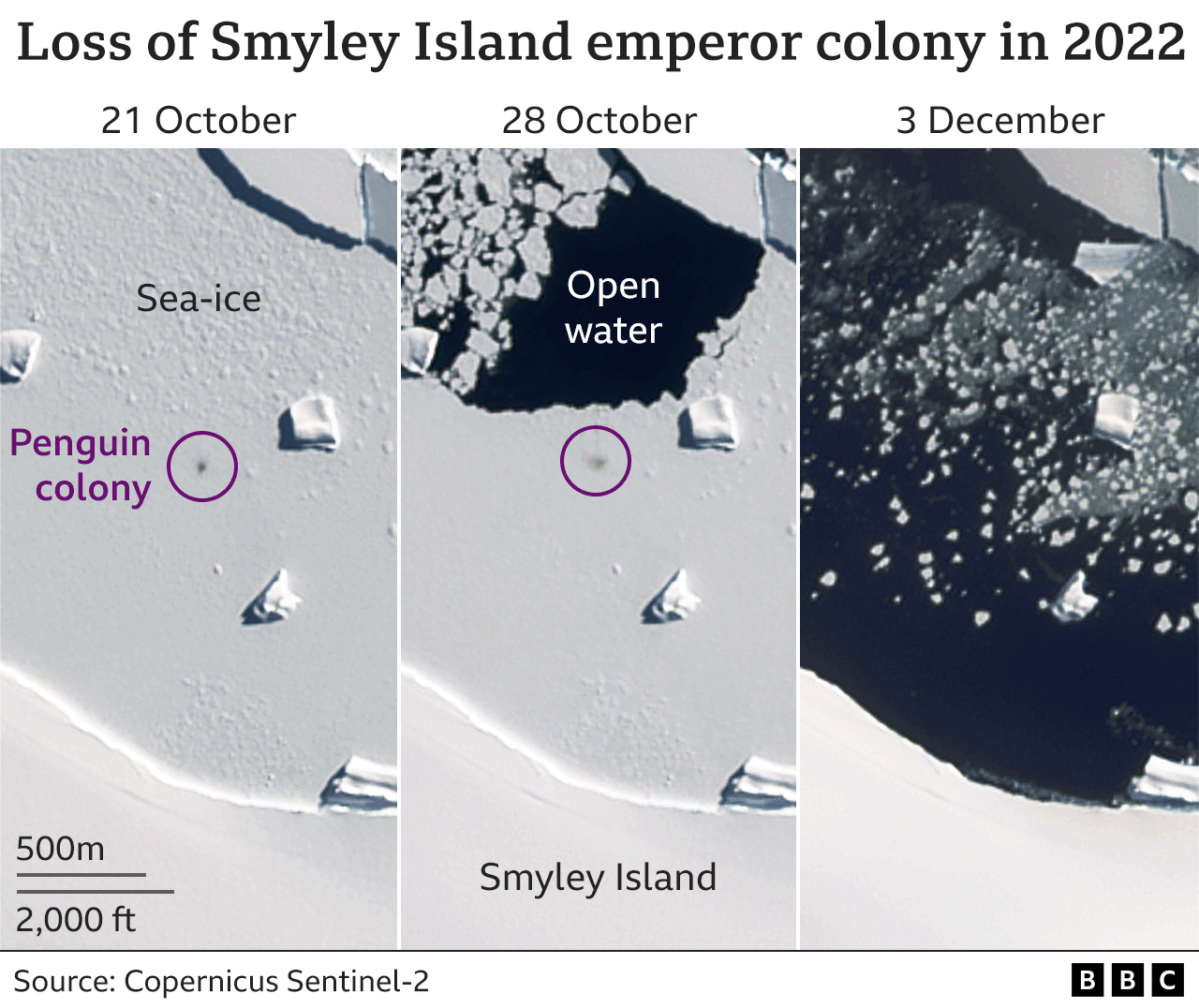

It was recorded by satellites.

Dr Peter Fretwell, from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), said the wipeout was a harbinger of things to come.

More than 90% of emperor penguin colonies are predicted to be all but extinct by the end of the century, as the continent's seasonal sea-ice withers in an ever-warming world.

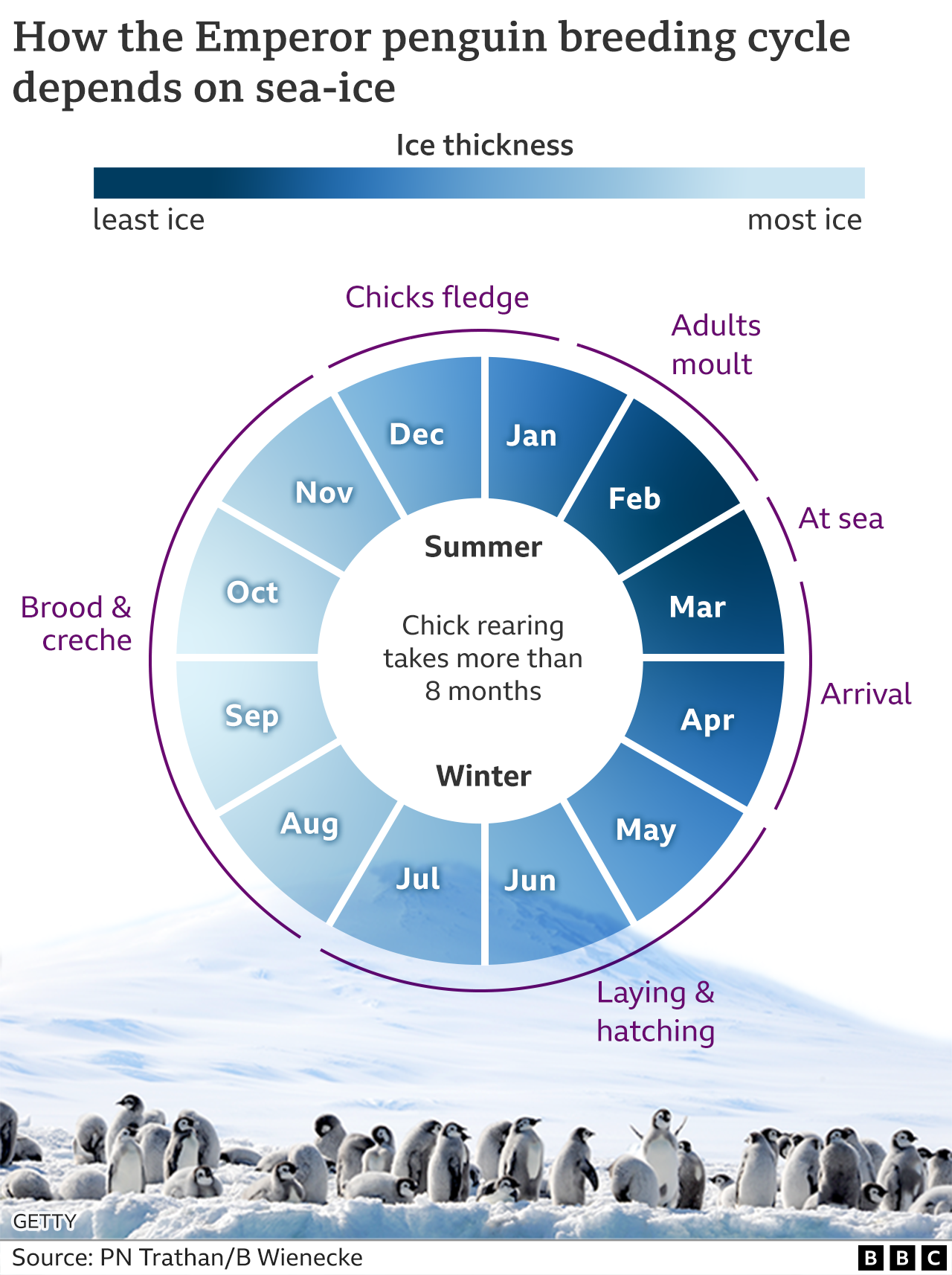

"Emperors depend on sea-ice for their breeding cycle; it's the stable platform they use to bring up their young. But if that ice is not as extensive as it should be or breaks up faster, these birds are in trouble," he told BBC News.

"There is hope: we can cut our carbon emissions that are causing the warming. But if we don't we will drive these iconic, beautiful birds to the verge of extinction."

- Earth in uncharted waters as climate records tumble

- Emperor penguin 'needs greater protection'

- Alone with 10,000 emperor penguins

Dr Fretwell and colleagues report the die-off in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

The scientists tracked five colonies in the Bellingshausen Sea sector - at Rothschild Island, Verdi Inlet, Smyley Island, Bryan Peninsula and Pfrogner Point.

Using the EU's Sentinel-2 satellites, they were able to observe the penguins' activity from the excrement, or guano, they left on the white sea-ice.

This brown staining is visible even from space.

Adult birds jump out on to the sea-ice around March as the Southern Hemisphere winter approaches. They court, copulate, lay eggs, brood those eggs, and then feed their nestlings through the following months until it's time for the young to make their own way in the world.

This normally occurs around December/January time, when the new birds head out into the ocean.

But the research team watched as sea-ice under emperor rookeries fragmented in November, before thousands of chicks had had time to fledge the slick feathers needed for swimming.

Four of the colonies suffered total breeding failure as a result. Only the most northerly site, at Rothschild Island, had some success.

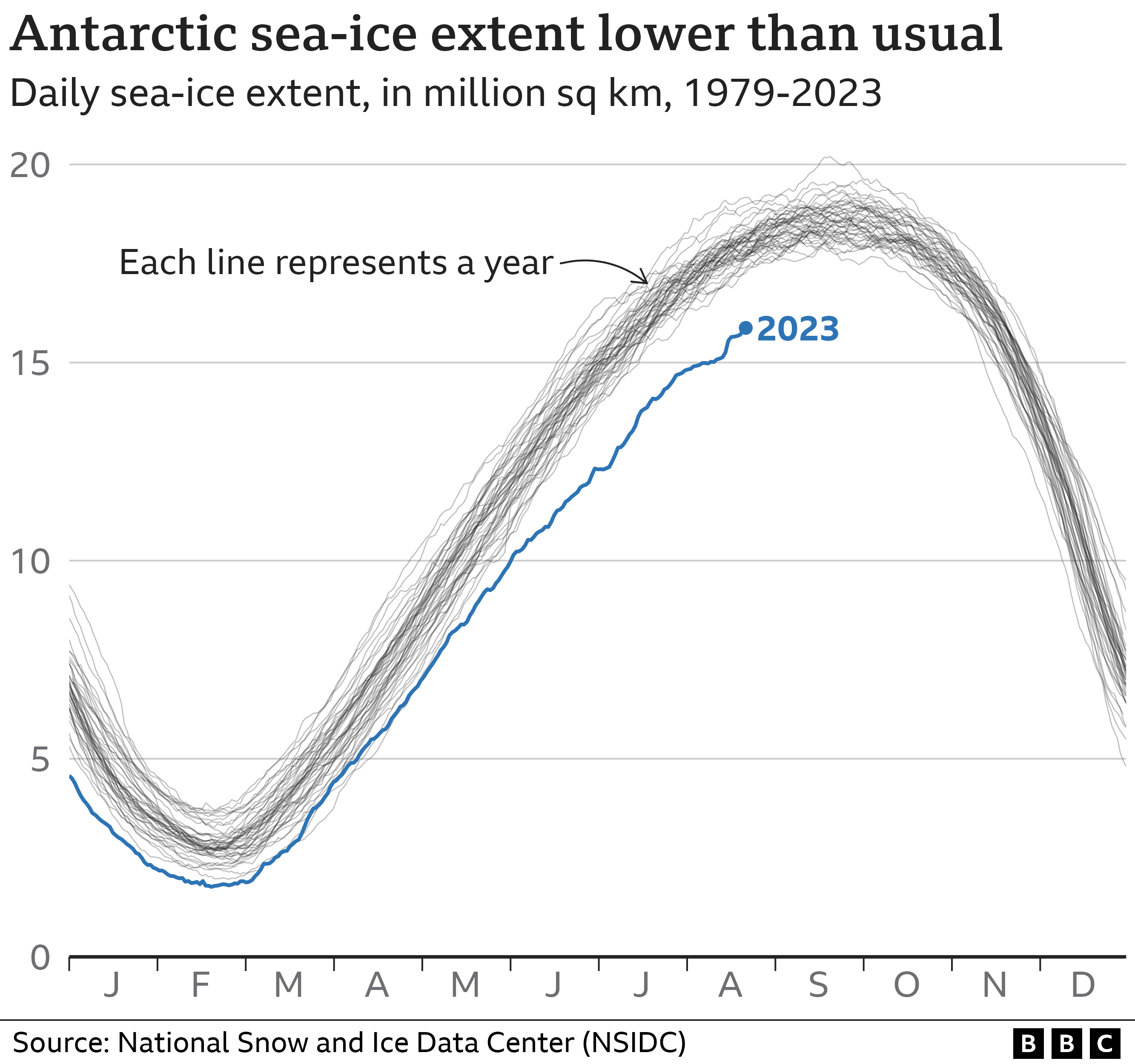

Antarctic summer sea-ice has been on a sharp downturn since 2016, with the total area of frozen water around the continent diminishing to new record lows.

The two absolute lowest years have occurred in the past two summer seasons, in 2021/22 and in 2022/23, when the Bellingshausen was almost completely devoid of ice cover.

What is more, the slowness of floes to form in recent months means the colonies will probably not be producing chicks for at least another year.

Winter maximum sea-ice extent, normally reached in September, will track far below where it would normally be.

Dr Fretwell and colleagues said the emperors were feeling the impacts of this shift in conditions. Between 2018 and 2022, roughly a third of the more than 60 known emperor penguin colonies were affected in some way by diminished sea-ice extent - whether that's ice forming later in the season or breaking up earlier.

At the other end of the planet, in the Arctic, the sea-ice has been in a decades-long, steady decline. The Antarctic in contrast seemed more robust. Up until 2016, it was becoming slightly more extensive year on year.

BAS colleague Dr Caroline Holmes is an expert on Antarctic sea-ice. She links the causes for the current decline to anomalously warm ocean water around the continent and a particular pattern of winds, which in the case of the Bellingshausen, has pushed ice back towards the coast, making it difficult to spread.

These were remarkable times, she said.

"What we're seeing right now is so far outside what we've observed previously. We expected change but I don't think we expected so much change so rapidly," she told BBC News.

"Studies in the Arctic have suggested that if we could reverse climate warming somehow, the sea-ice in the polar north would recover. Whether that might also apply in the Antarctic, we don't know. But there's every reason to think that if it got cold enough, the sea-ice would reform."

Currently, emperors are classified as "Near Threatened" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the organisation that keeps the lists of Earth's most endangered animals.

A proposal has been made to lift emperors into the more urgent "Vulnerable" category because of the danger posed by climate warming to their way of life.

Photograph: GETTY IMAGES