Climate change: Satellite maps warming impact on global glaciers

Scientists have obtained their best satellite assessment yet of the status of the world's glaciers.

Europe's Cryosat spacecraft tracked the 200,000 or so glaciers on Earth and found they have lost 2,720bn tonnes of ice in 10 years due to climate change.

That's equivalent to losing 2% of their bulk in a decade.

Monitoring how quickly glaciers are changing is important because millions of people rely on them for drinking water and farming.

The world's glaciers are distributed across all latitudes, not just at the poles. A few hundred are routinely measured at ground level - the best way to assess them. But for the vast majority, observation from space is the only way to keep an eye on how they are responding to climate change.

It's important that we do that. Like the broader ice sheets, their whiteness reflects sunlight and helps cool the planet.

And in many parts of the globe, glaciers also function as critical water reservoirs. More than 20% of the world's population is thought to be dependent in some way on summer melt waters that flow from glaciers - for drinking, for agriculture and to drive hydropower stations.

- Accelerating melt of ice sheets now 'unmistakable'

- Satellites now get full-year view of Arctic sea-ice

- A really simple guide to climate change

Cryosat is a veteran European Space Agency Earth observer.

It carries an instrument called a radar altimeter, which sends down microwave pulses to trace variations in height along the planet's surface - and in particular the changes in elevation of ice fields.

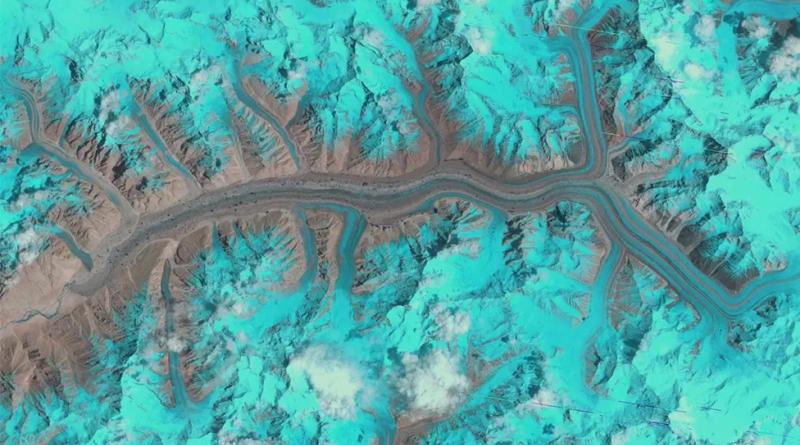

This type of instrument works really well when monitoring the gentle undulations in the interior of Antarctica and Greenland. It finds it more tricky to measure the ice that runs across rugged terrain, such as in steep-sided valleys.

But advances in data processing have enabled scientists to effectively increase the resolution and robustness of Cryosat's vision so that it can now track developments even in those hard-to-see locations.

The study, reported on Wednesday in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, has applied this approach to the spacecraft's entire data archive to produce a global glacier assessment.

The satellite's observations indicate the vast majority - 89% - of the ice loss seen between 2010 and 2020 was due to melting in an ever warmer atmosphere.

Only 11% of the loss was the result of glaciers experiencing melting or increased flow because their fronts terminate in warmer ocean or lake waters.

Alaska's glaciers have experienced the greatest losses. They've been losing more than 80bn tonnes a year, which equates to about 5% of the total ice volume in the region during the 10-year study period.

This is very much an effect of warmer air temperatures.

Places where glaciers appear to be eroding and moving faster because their fronts end in warmer waters include the Arctic - at Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago - and in the Russian sectors of the Barents and Kara seas.

Increasing ice discharge into the ocean accounts for over 50% of mass loss in these areas.

"This is a consequence of what is called the 'Atlantification' of the Arctic," explained Noel Gourmelen from Edinburgh University, UK.

"Usually, the surface waters of the Arctic Ocean are cold and fresh, but increasingly in some of these places the surface waters are becoming more salty and warmer as currents move up from the Atlantic. And this means glaciers are dumping more ice into the ocean," he told BBC News.

This, of course, will add to sea-level rise which already threatens low-lying communities.

Cryosat is an old spacecraft that has worked far beyond its design life. Scientists hope to get a few more years of operation from it but there's a recognition that it could fail any day now.

The European Union is planning a long-term satellite series inspired by Cryosat, given the code name currently of Cristal.

"What we've shown you can do with Cryosat to measure glaciers worldwide augurs well for the Cristal mission," said Edinburgh colleague Livia Jakob.

Ms Jakob, who led the research from her remote sensing company Earthwave, has been discussing its implications in Vienna, Austria, at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly, one of the world's biggest gatherings of Earth scientists.

cover photo: F.PAUL/NASA/USGS