Bridgewater advocates increased Africa investment to accelerate growth

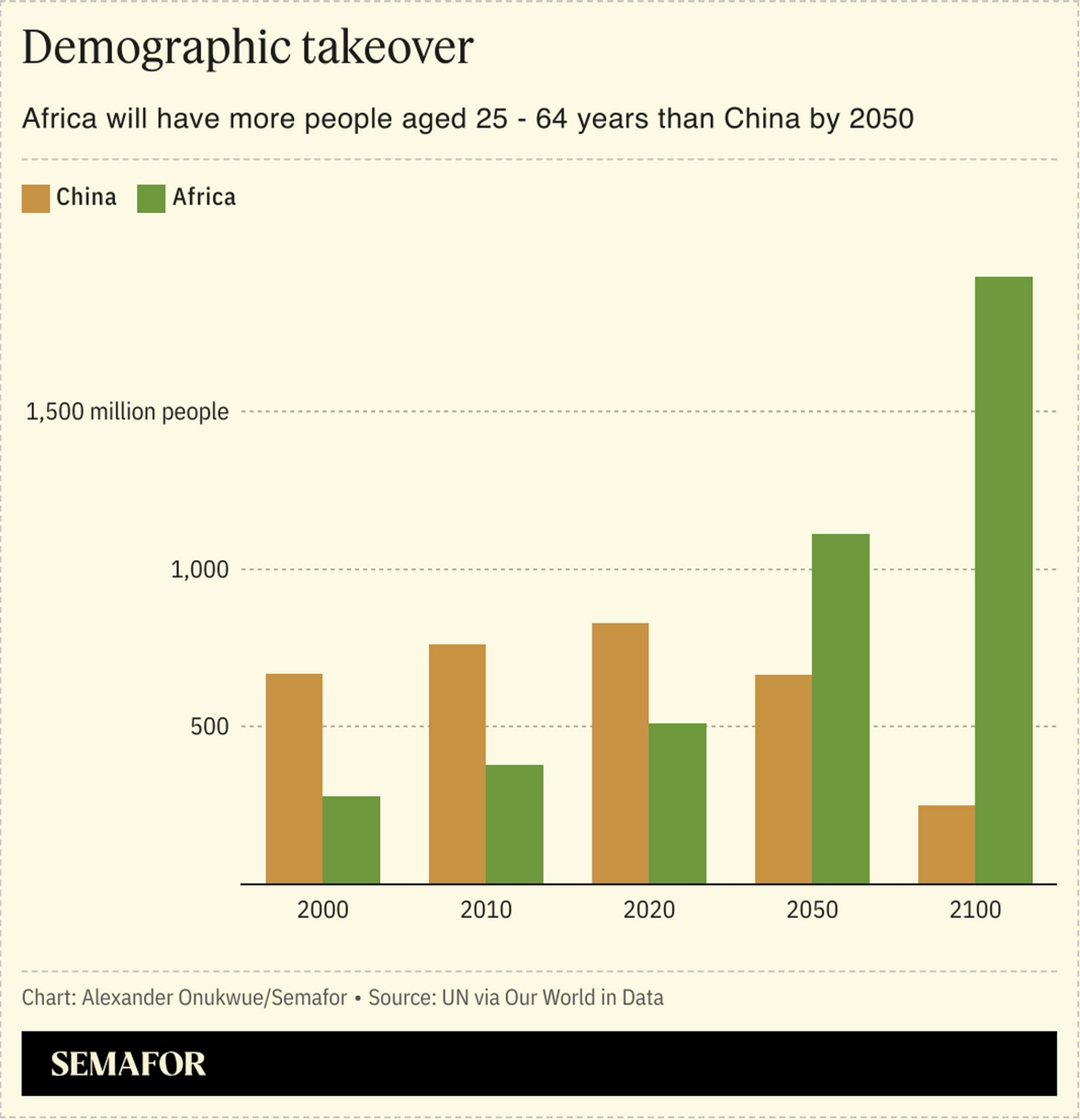

Sub-Saharan Africa’s march towards having more people of working age than China in the coming decades demands an urgent expansion of investment to avoid leaving the region behind, the world’s biggest hedge fund Bridgewater Associates has warned.

A new report by the hedge fund, seen exclusively by Semafor Africa, estimates that sub-Saharan Africa requires a doubling of current investment to at least 30% of gross domestic product “to achieve a much steeper development trajectory.”

But the path to this increase requires concerted efforts to dispel global investor perceptions of high risk in the region by strengthening weak institutions and human capital, and breaking down policy fragmentation from one country to another that shrinks the market opportunity.

Bridgewater forecasts Africa’s long-term future economic growth at a maximum of 5.5%, based on a “positive but low” long-term output-per-worker growth of 2%, and working-age population growth of about 3%.

The estimates “suggest that, unless there is significant and persistent additional action, the region will not achieve the growth levels needed to meaningfully address the current imbalances,” the report said.

The report recommends ramping up investments by development banks, particularly the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), to address challenges in poor countries.

Bridgewater entered a partnership with Global Citizen to support the World Bank’s 21st IDA replenishment.

Based in Washington DC, the IDA offers grants and low-to-zero interest loans to the world’s 75 poorest countries, 39 of which are in Africa. Repayment periods for the loans stretch up to 40 years. Ethiopia and Nigeria have been in the top five of IDA borrower countries since 2015 with nearly $35 billion borrowed.

IDA funds are replenished every three years with donations from mostly high and middle income governments, other multilateral lenders and private investors. Last December, in Tanzania, World Bank President Ajay Banga asked donors to raise $100 billion for IDA’s 21st fund.

The most recent raise of $93 billion in 2021 was the organization’s largest since it was founded in September 1960. African heads of state pushed in April to raise the mark to $120 billion but Bridgewater’s call to double current investment levels requires a $180 billion pool.

Banga’s ascent from the private sector to lead the World Bank last year was received with cautious optimism by Africa watchers. His nomination sparked renewed calls for the bank to be more relevant to and discerning of the continent’s actual development priorities. The former Citigroup banker and Mastercard chairman said his approach is to provide resources that seed long-term benefits for Africa, rather than short-term interventions that only act as band-aids.

“What we’re trying to do, instead of spreading the peanut butter thin and doing everything that everybody wants, is to pick things that will make a quantum difference in a finite time to change the trajectory of what’s going on in Africa,” Banga said during a private event attended by Bridgewater staff.

The region’s governments have a role in financing this change but “the only way to get trillions to work is by getting the private sector to see a rational return on their investment,” he said.

Expanding funding to multilateral lenders ensures investment can be directed to poor countries with limited domestic resources, where the private sector has little incentive to fund projects with high social returns but “limited capturable profits,” Bridgewater’s report argues.

France, Germany, the UK and other top donor countries to lenders like the IDA are “grappling with donor fatigue” as conflicts in Europe and the Middle East increase constraints on aid budgets.

Half of the world’s 75 poorest countries have seen a widening income gap with the wealthiest economies for the first time this century, the World Bank said in a report published in April.

“The big regions in the world, the developing world… massively matter in the long term to anybody trying to understand where the world is headed in any serious way,” said Nir Bar Dea, Bridgewater’s chief executive officer, in a recent speech.