After asking ‘What about the climate?’ for 14 years, I’m standing down as an MP. But I have reasons to be hopeful

When I entered parliament back in 2010 as the first Green MP, I used every possible trick in the book to push the environment up the UK’s political agenda. In the early days, progress was agonisingly slow. Simply making the case that Britain should be powered by renewables, not fossil fuels, was a daily battle. Every single budget, I would stand up and ask the same question: what about the climate? And then, quite quickly, things finally began to change.

I’ll never forget the moment I realised the environment movement had finally entered the political mainstream. The shift dawned on me during the school strikes five years ago, which brought over a million people worldwide out on to the streets in protest. I stood on top of a makeshift platform on a fire engine outside parliament and saw a vast crowd of young people, stretching as far as the eye could see, demanding climate justice and action.

It was a moment of uprising. And in those crowds, I found the evidence that it was no longer just specialist environmental groups speaking out. Students, scientists, lawyers, grandparents and artists: activists of all ages and political persuasions were coming together to exert pressure on the government to act. The climate crisis could be denied no longer – politicians had to respond. Suddenly, we went from an era when David Cameron dared to dismiss the problem as “green crap”, to one in which environmental challenges have rocketed to the top of the political agenda. MPs across all parties have now come together to declare a climate emergency, and in 2019 the UK became the first G7 country to legislate for net zero by 2050.

And, depressing as it is to see the Tories now setting that consensus alight in a desperate lurch towards the hard right, not to mention Labour rowing back on its vital £28bn annual climate commitment, we shouldn’t underestimate just how much we have changed the conversation for good in this country. Because while some politicians might now be wavering and pedalling backwards, the public are not. The environment now consistently ranks among Britain’s top priorities.

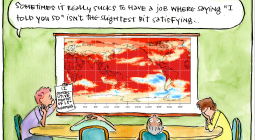

But stepping down now from parliament, I can’t help but reflect on how much further we have to go if we’re to avert environmental disaster. We are, to quote the UN secretary general, on a “highway to climate hell”, hurtling towards a global catastrophe of temperatures nearly three degrees warmer. At such a critical juncture, just changing the conversation isn’t enough – and nor is changing the government. Even under a new Labour administration, if we continue with business and politics as usual in the next parliament, we will quite simply be colluding in signing our own environmental death warrant.

What we need now is to tear up the political rulebook that has got us to this point. It isn’t enough for the Greens to get a foot in the door of our broken political system – we must work to transform it entirely, with an urgent replacement of our closed-shop electoral system that allows just two parties to control and dominate political decision-making.

We also need to organise within communities held back by the government and support people who put their bodies, their careers and their livelihoods on the line to avert environmental disaster. And we need to challenge and dismantle the all-consuming, all-destroying national obsession with defining our prosperity not by our health and wellbeing, or that of our environment, but by the unending quest for GDP growth.

That’s not just a critique of corporate capitalism, it’s an urgent and practical challenge. Because the reality is that although the transition from fossil fuels may be under way, it isn’t happening anywhere near fast enough. Nor with anything like sufficient attention to who wins and who loses. And that’s why some of what we’ve achieved in the past 14 years is under attack. There is no serious route out of the triple crises of climate, nature and inequality unless we rapidly mobilise and redistribute vast flows of finance on a national and global scale.

The rise of the far right across Europe is a warning of what happens when fear is whipped up among a population at the sharp end of economic decline. If Labour doesn’t now rise to the moment with bold policies and – crucially – a properly resourced transition; if it doesn’t urgently rethink the fiscal straitjacket it has chosen to strap itself into, it might win this election, but at the risk of laying the table for a resurgent far right.

We cannot allow the very poorest people to pay the highest price and tell people, for example, that they need to change how they heat their homes, without guaranteeing that the costs of that will be borne by us collectively and paid for by those with the most. And we can’t ask the poorest and most vulnerable countries to suffer the worst impacts of the climate crisis as we – a rich, industrialised nation – debate whether we’ll even do the bare minimum of getting to net zero by 2050.

These are the things at stake in this election – and small incremental change just won’t cut it. The gap between what’s scientifically and ethically essential, and what’s currently deemed to be politically possible, needs to close. And we will need a new generation of Green MPs in parliament more than ever, demanding that the next government is bold and brave enough to offer real hope and real change.