Greenpeace accuses Russia of ‘unprecedented escalation’ if it restarts Zaporizhzhia reactors

Vast nuclear power plant has been on the frontline of the war since its capture in March 2022

Greenpeace has accused Russia of threatening Ukraine and the west with “an unprecedented escalation” if Moscow tries to restart reactors at the occupied Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station.

The pressure group’s warning came a day after Rafael Grossi, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), met the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, in Sochi to discuss nuclear safety and the plant on the frontline of the Ukraine war.

Grossi told Russia Today on Tuesday that he discussed with Putin the possibility of restarting the plant, which Greenpeace said would create an unprecedented risk if any of the six reactors were restarted as has been suggested by Russian officials.

Shaun Burnie, a nuclear specialist with Greenpeace Germany, said: “No nuclear regulations exist anywhere in the world that permit a nuclear plant to operate on the frontline in an active war zone.”

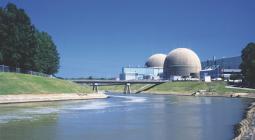

Captured by the Russian invaders in the early stages of the war in March 2022, the vast Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant has been on the frontline of the war ever since. It is sited on the Dnipro River in central Ukraine and Ukrainian forces occupy the bank opposite, leaving the plant in the sights of both sides’ militaries.

Initial aspirations by Russia to connect the reactors to its own energy grid were abandoned and all six of its reactors were put into various states of shutdown. But recent comments from officials have suggested a new attempt to restart nuclear energy generation may take place later this year.

Yuriy Chernichuk, the Russian-appointed director of the site, told the plant’s staff newsletter at the end of December: “Next year is an anniversary year for the station and the station is determined to work at full capacity.”

Last month, Grossi said he would seek to understand Russia’s intentions, while on Tuesday the nuclear watchdog cautioned Moscow when asked in Sochi if some or all of the reactors were going to be restarted.

“I have been drawing the attention of my Russian counterparts to the fact that any such action would require a number of considerations,” Grossi said. “First of all, this is an active combat zone, and this cannot be forgotten. Secondly, this plant has been in shutdown for a prolonged period of time.”

Nevertheless, the IAEA director general did not absolutely warn against restarting energy generation on the site, and said that to do so would “require a number of safety assessments to be performed” by the Russian occupiers.

The Kremlin released opening remarks of the meeting with Grossi. In them, Putin did not mention any plans for Zaporizhzhia, but did say “it is very important, on a planetary scale” to ensure “nuclear energy safety and compliance with safety standards throughout the world”.

A report from the RIA Novosti news agency reported that Grossi had described the talks as “tense” but a spokesperson for the IAEA denied the assertion. As well as meeting Putin, Grossi also met Alexey Likhachev, the director general of Rosatom, the Russian state-owned energy company now running the plant.

Greenpeace accused Grossi of being complacent, and said restarting any of the reactors should be completely ruled out. “The IAEA must not play the role of pretend regulator in overseeing a Russian nuclear timebomb, but instead must make clear that safe operation is impossible,” Burnie said.

The environmental pressure group said that an operating nuclear reactor would inevitably run at a reduced margin of safety on the frontline, and there was a particular concern whether Rosatom could ensure there was enough cooling water available to safely operate even a single reactor.

An analysis by Greenpeace says that Russia would need to construct a fresh pumping station to ensure there was enough cooling water available, because the Dnipro no longer flows into the cooling reservoir on site. The river dramatically shrunk in the area after the Nova Kakhovka dam downstream was blown up last June.

Five of the nuclear reactors at the plant, Europe’s largest, are in a cold shutdown, where the reactors are running at a temperature below boiling point. A sixth is in hot shutdown, to produce steam and heating needed for the site.

IAEA inspectors are present on site, although there have been criticisms about restrictions placed by Russia on their access, but even in shutdown its situation remains fragile. Russian forces are believed to be present in the plant, although conflict in the area has not been intense.

There are only two out of 10 prewar power lines remaining to power the reactor cooling system. On eight occasions over the last 18 months, the IAEA has said, both lines went down, requiring the nuclear plant to rely on emergency backup generators to prevent the reactors from gradually overheating.

Cover photo: The Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. Initial aspirations by Russia to connect the reactors to its own energy grid were abandoned. Photograph: Alexander Ermochenko/Reuters